Workplace deaths raise questions about OSHA experiment in self-regulation

By Ariella Cohen, crossposted from The Lens. In January 2002, a mound of powdery chemical catalyst used to make gasoline collapsed on a worker doing routine cleanup at the Marathon Ashland Petroleum refinery in Garyville, La.

Within minutes, the contract employee, from Colfax, was completely engulfed in the toxic chemical and struggling to get free. Before help arrived, the face seal on the man’s helmet broke, allowing fresh air to hit the catalyst and ignite. “Employee #1 was killed as a result of chemical burns,” reads the Occupational Safety and Health Administration report on the death, which was tagged a “housekeeping” issue. The incident report ends with no violations listed and no penalties imposed.

Photo credit: Andy Cook/ The Lens

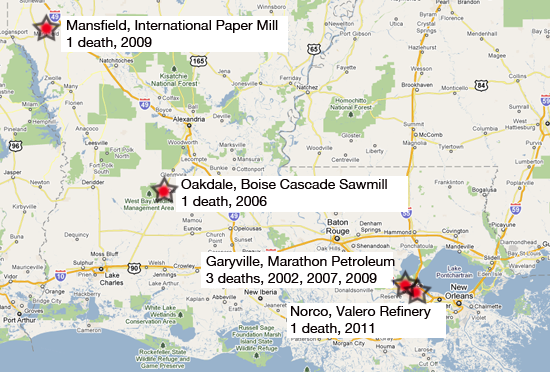

Marathon, which would experience another fatal accident in 2007 and again in 2009, has been considered by the federal government to be one of the country’s safest places to work for nearly two decades, one of 2,434 across the country certified by OSHA as a Voluntary Protection Program site.

That status makes the refinery part of an elite group of businesses that serve as ambassadors between industry and the agency’s safety inspectors. In exchange for professing a commitment to safety and carrying that message to private-sector peers, program members get a three-to-five-year exemption from routine OSHA inspections and a friendlier relationship with the feds, not to mention bragging rights useful to the public relations department. Created in 1982 as part of the Reagan Administration’s effort to shrink the federal bureaucracy, the program was an experiment in industry self-policing.

After two decades of slow growth under Reagan and his White House successors, George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, the self-enforcement program took off during George W. Bush’s eight years in Washington.

One of the few OSHA initiatives spared cuts during the Bush administration, the program was promoted as a way to encourage employers to voluntarily comply with safety standards at a time when regulations and enforcement efforts were being steadily rolled back. Under Bush, the number of workplaces blessed with the OSHA model-workplace certification tripled nationally, despite warnings from government auditors that such ambitious expansion could threaten the program’s integrity.

Today, the program continues to grow and Congress is considering legislation, co-sponsored by U.S. Sen. Mary Landrieu, D-La., that aims to expand it even further. In addition to codifying the program and expanding access to it, the legislation would prevent OSHA from imposing the user fee it proposed last year to cover increased inspections of participating workplaces. Current rules call for inspections only in the event of a fatality or if a complaint is filed.

If the proposed legislation becomes law, Louisiana – which already has more self-regulated sites than any state other than Texas, Pennsylvania and Ohio — is expected to see a jump in participation.

“Louisiana has one of the largest number of VPP sites in the U.S., and from my experience working with companies in the state, those companies that are in have a true commitment to workplace safety and health,” said Davis Layne, executive director of the Voluntary Protection Program Association, a nonprofit trade organization. “Many other companies are now seeing that value and trying to get involved.”

The commitment to safety may be sincere, but evidence that the program is actually achieving its goals is hard to come by. The deaths at Marathon are not the only fatalities at these so-called model workplaces. Since 2000, at least 74 workers have died at certified sites and agency investigators found serious safety violations in at least 47 cases, according to records examined by The Lens in collaboration with Center for Public Integrity’s iWatch News. In Louisiana, there have been six deaths since 2000, including the three at Marathon in Garyville and two at other facilities that were linked to serious violations of their safety code. None of the Louisiana deaths resulted in companies losing model workplace status.

Critics of the federal government's Voluntary Protection Program say that fatal accidents should not be tolerated at these so-called models for workplace safety.

Indeed, the disconnect between the Voluntary Protection Program’s goals and its results is especially stark in Louisiana, where a large petrochemical industry puts workers in daily contact with life-threatening risks that are not measured by the program. The big problem, program critics contend, is that the potentially catastrophic risks inherent in refinery operations aren’t meaningfully reflected in the personal-injury data that is the program’s primary metric.

“In a refinery, not fixing a pipe or repairing a machine can lead to a major explosion and a slip-and-fall rate is not going to help you know if that repair or maintenance was done,” said Celeste Monforton, a former OSHA policy analyst who now is a lecturer in environmental and occupational health at George Washington University.

The agency’s records lend validity to Monforton’s concern. Petroleum refining facilities account for only about 7 percent of OSHA’s model workplaces in Louisiana – six out of 107 sites. Yet four of the last decade’s six fatalities – 67 percent— occurred in those petrochemical facilities. Nationally, at least 11 of the 74 site- recorded fatalities between 2000 and 2010 — 15 percent — happened at refineries, all of them in Louisiana or Texas, OSHA records show. Additionally, these facilities increasingly depend on contract workers – like the man who died of chemical burns at Marathon’s Garyville plant — whose injuries or days lost are simply omitted from the personal injury rate average that serves as the program’s primary metric for measuring workplace safety. This means that refineries could have a higher rate of on-site injury than allowed by program standards, yet still be certified because a sector of its workforce isn’t factored into the equation.

In March, a contract worker at Valero Energy’s facility in Norco, a certified program participant, fell from a ladder to his death. A malfunction in the plant had exposed the worker, Victor Rodriguez, 30, to dangerous levels of the toxic gas hydrogen sulfide in the minutes before his fall.

His family is now suing Valero and the contracting company that employed him for wrongful death.

“What happened was a breakdown in the process safety management,” Byron Buchanan, a lawyer for the deceased contractor’s family, said.

But while the Houston lawyer contends that the fatal accident was preventable, and possibly indicative of a larger weakness in the refinery’s process management system, it’s unlikely to affect Valero’s status as a model for workplace safety or cost it money in fines, analysis of OSHA inspection data shows. Among the fatalities that previously occurred at federally certified sites in Louisiana, three of the five complete accident investigations — 60 percent of the total and all of them at Marathon — resulted in no penalties.

While refineries avoided fines, wood and paper companies weren’t so lucky. After a worker was killed at the International Paper mill in Mansfield, OSHA fined the company $10,000 for two separate violations. No summary of the accident was included in OSHA’s investigation but records show the violations were for failing to maintain proper guard rails and other safety mechanisms. The 2009 fines remain outstanding, though the company told OSHA it had fixed the problems in 2010.

In Oakdale, a Boise Cascade sawmill was assessed $4,410 after an employee was fatally struck by a tractor-trailer while walking to his workstation. “The intersection of the drive aisle was not marked or controlled by signals or stop signs,” an OSHA inspector noted in the accident investigation summary. The lack of traffic signage led to an initial fine of $6,300.The agency later settled with the company for $4,410 in penalties.

OSHA did not respond to a request for information about the mill deaths. It was not, however, the agency’s first time fielding questions about a worker death at a safety-certified International Paper mill.

In 2008, a catastrophic boiler explosion at a mill in Vicksburg, Miss., killed one worker and injured another 22, leaving at least three in medically-induced comas for months while doctors treated serious burns. In a subsequent investigation OSHA discovered that the Tennessee-based company had ignored an internal memo outlining recommendations that, if followed, would have prevented the explosion or minimized risk to workers, according to records examined by the Center for Public Integrity’s iWatch News. OSHA, in its investigation, alleged violations of safety standards that program members are expected to exceed, yet the company did not lose certification.

Texas refineries have been less successful than their Louisiana counterparts in avoiding fines following fatalities, OSHA records show, perhaps in part because the deaths at program-certified refineries in Texas have been associated with more catastrophic failures of systems and machinery. In total, 54 percent of fatality investigations at Texas refineries — four out of seven — resulted in fines compared to zero in Louisiana.

What the two states have in common, however, is that none of the fatalities resulted in an establishment losing OSHA certification as a model for safety. After a worker was killed and another seriously injured by a preventable boiler explosion at a Valero refinery in Texas City, for instance, OSHA issued the Voluntary Protection Program participant a citation. The 2009 blast had thrown one of the workers under a stainless steel tank, causing “fatal blunt force trauma,” the accident report reads. Valero hasn’t paid its $4,500 penalty, or suffered a fall from grace as part of the model-workplace program.

At Marathon in Garyville, another worker died after mistakenly driving his pickup into a wastewater retention pond on the refinery’s grounds. By the time co-workers answered his radio call for help, the technician’s Ford F-150 was completely submerged. “Employee #1 was found at approximately 3:00 a.m. on September 1, 2007, drowned in the pond,” reads the OSHA report. Again, no violations were found and no fines imposed on the refinery, which was certified as a model workplace in 1994. In the report’s concluding lines, an inspector notes that there are no lights in the area. No penalties were paid and the site remains part of OSHA’s model program.