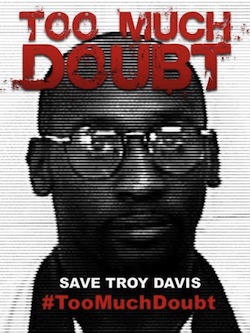

What did we lose when we lost Troy Davis?

The night Troy Davis died, I stood in front of the Louisiana Supreme Court building with 100 other people, including my 10-year-old son, praying that the higher court would do the right thing and grant him a stay of execution. As I left the vigil to attend a meeting with a group of formerly incarcerated persons, I remembered the first vigil I attended in New Orleans, in April of 1997, for the execution of John Ashley Brown. I remembered the dejection and anger that I had felt that night as a group of us trudged away from Jackson Square, the site of our vigil, and also of lynchings during the post-Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras of our city. Comparing those two nights, I knew this felt different. I knew I felt more hopeful, and I knew it wasn’t because Troy, a man so many of us believe was innocent, had been granted a few extra hours to live. Somehow, I felt changed.

The night Troy Davis died, I stood in front of the Louisiana Supreme Court building with 100 other people, including my 10-year-old son, praying that the higher court would do the right thing and grant him a stay of execution. As I left the vigil to attend a meeting with a group of formerly incarcerated persons, I remembered the first vigil I attended in New Orleans, in April of 1997, for the execution of John Ashley Brown. I remembered the dejection and anger that I had felt that night as a group of us trudged away from Jackson Square, the site of our vigil, and also of lynchings during the post-Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras of our city. Comparing those two nights, I knew this felt different. I knew I felt more hopeful, and I knew it wasn’t because Troy, a man so many of us believe was innocent, had been granted a few extra hours to live. Somehow, I felt changed.

I arrived at the meeting site, the Resurrection After Exoneration (RAE) house and everyone there was talking about the impending decision over Troy Davis’ life, the protests around the world, the hundreds of others on death row, the number of individuals on death row who were found to be innocent (138 to date, nationwide.) Derrick Jamison, number 119, was standing next to me. He talked about how they had tried to execute him in Ohio, he had spent 17 years imprisoned for a murder he did not commit. On a speaking tour against the death penalty, Derrick met Troy Davis’ sister. “Despite battling cancer, she was out there fighting for her brother’s life to the end. And she won’t stop.” Living in New Orleans, Derrick now works closely with other exonerees through RAE. One of them is RAE’s founder and executive director, John Thompson.

I spoke with JT the following morning, when he came into the office our respective organizations share with the Innocence Project of New Orleans. Having had his own experience with the Supreme Court, John hoped this enormous failure of justice would serve as a wake up call to the general public. “The Supreme Court just made those 12 people killers. All of us really… for believing in this. People expect them to be reasonable, to be the authority, but we have to realize this isn’t reasonable. We can’t just go along with it. We can just let them speak for us… They don’t care who is innocent. They didn’t care what was the cost. We have to wake up and stop believing that they’ll do the right thing. They won’t do the right thing, especially if we don’t stand up.”

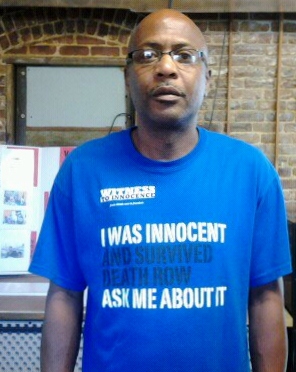

I’ve worked with JT a few years now and I was thinking last night about how much he has enriched my life, how much I have learned from him. I was thinking about how important it is to me that my son see these men around him who fight so hard for others; Who, despite the enormous unfairness of what they’ve been through, their lives are about helping others, helping those that are still not free. I can’t imagine how different my life would be, how much poorer my community of social justice changemakers, if the state had proceeded on just one of the three execution dates that they set for JT.

I’ve worked with JT a few years now and I was thinking last night about how much he has enriched my life, how much I have learned from him. I was thinking about how important it is to me that my son see these men around him who fight so hard for others; Who, despite the enormous unfairness of what they’ve been through, their lives are about helping others, helping those that are still not free. I can’t imagine how different my life would be, how much poorer my community of social justice changemakers, if the state had proceeded on just one of the three execution dates that they set for JT.

Image: John Thompson.

One of JT’s closest friends and colleagues is my boss and mentor, Norris Henderson, the founder and director of VOTE (Voice Of The Ex-offender). Norris was wrongfully incarcerated for 27 years. While incarcerated, he became a fierce advocate for the legal rights of prisoners and for the wholecloth transformation of the criminal justice system. Thursday after Troy Davis’ execution, Norris walked into the office with a disgusted look on his face.

“I just can’t believe it. That’s why this whole system has to be torn down. I think he might have been used as a pawn in this whole system,” Norris said, pointing out that Davis was executed the same day as the execution in Texas of a white supremacist who was convicted of murdering an African American man in a hate crime. “It makes us realize how much work we have left to do. We have a long way to go. “What did we solve?” by killing Troy Davis, he asks. “And in a case where there was so much doubt. Troy was very likely innocent. Now you can’t undo this, you can’t bring him back now.”

We can’t bring Troy back. And we can’t spend too long lamenting who he would have been to us, had he been exonerated and set free, as I did on the night he died, tears welling up in my eyes as I thought of his exhortation to all of us to continue fighting. There are too many Troy Davises still with us, too many people still embattled by a criminal justice system rooted in vengeance, slave labor and racism. We have to make sure that we continue to fight so that they won’t become another Troy Davis, martyr and symbol, but that they can take their place among the ranks of Derrick Jamison, John Thompson and Norris Henderson, living warriors who inspire us, fill us with hope and urge us to be our best selves, bigger than the greatest injustices we’ve faced.

Editor's note: In the wake of Troy Davis's execution in Georgia, Bridge the Gulf asked a number of our contributors and leaders in the social justice movement to share some of their reflections. This is the second of several pieces to be posted in the coming week.

Related posts: Talking to my son about Troy Davis

----------

Rosana Cruz is Associate Director of VOTE (Voice Of The Ex-offender). Previously Rosana worked with Safe Streets/Strong Communities and the National Immigration Law Center. Prior to joining NILC, she worked with SEIU1991 in Miami, after having been displaced from New Orleans by Katrina. Before the storm, Rosana worked for a diverse range of community organizations, including the Latin American Library, Hispanic Apostolate, the Lesbian and Gay Community Center of New Orleans, and People's Youth Freedom School. Rosana came to New Orleans through her work with the Southern Regional Office of Amnesty International in Atlanta.