In recovery from Southern tornadoes, fault lines of inequity show

Two days after a tornado tore through Eupora, Mississippi, Cherraye Oats set out with her daughter Courtney to get tarps for their neighbors’ battered homes. Oats’ house was spared, but the mobile home 20-year-old Courtney rented was destroyed. “If my daughter had not spent the night with us, we probably would have been burying her.”

Two days after a tornado tore through Eupora, Mississippi, Cherraye Oats set out with her daughter Courtney to get tarps for their neighbors’ battered homes. Oats’ house was spared, but the mobile home 20-year-old Courtney rented was destroyed. “If my daughter had not spent the night with us, we probably would have been burying her.”

The nearest disaster response center was several miles away at the fire station in Cumberland, a predominantly white town, and no one was bringing supplies out to their low-income African American and Latino community.

“The Black families were kind of just left alone out there,” recalls Oats, who is a Registered Nurse and a local organizer with the Fannie Lou Hamer Center for Change.

When they arrived at the fire station, a young man started to assist them. But Oats says he was called away by another man, Johnny Alford, who appeared to be working for the Webster County Emergency Management Agency. She says that next Alford hissed, loud enough for them to overhear, “What do them black rats want?”

Courtney says she wheeled around to face the white man and be sure she was hearing him right, when he repeated it to her face, “You, you black rat – what are you doing here?”

When Cherraye calmly explained they were there to help neighbors in need, he told her she could take just four tarps, “Cut them in half if you need to” – the rest were being held for families in Cumberland.[1]

Six months after this run-in with blatant racial discrimination in the tornado relief efforts, Cherraye and Courtney Oats say the recovery process also shows signs of inequality. “I just feel like low-income and African American families have fallen through the cracks,” says Cherraye.

Courtney, now 21, is still staying with her mother while she looks for a place to live. After weeks of frustrating back and forth with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the agency still has not approved her application for temporary rental assistance. Courtney begins to cry as she talks about her growing exasperation,

“I just want people to listen to us. I’m still trying to get back on my feet. I know my mother loves me, but… she has a house full of people. I feel like a strain… Every time I call [FEMA], they say ‘you need to do this, this, and this.’ And then I do it, and nothing is right.” Damage in Eupora, Mississippi. Photo by Cherraye Oats.

******

The tornado that destroyed Courtney Oats’ home was one of 305 that struck the U.S. south about six months ago. The outbreak, from April 25th to 28th 2011, killed more than 300 people, and made thousands homeless. In Alabama, the hardest-hit state, FEMA says 88,000 people registered for assistance.

“People are slowly recovering and rebuilding,” says John Zippert, director of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives. From its base in southwest Alabama, the Federation has been supporting tornado survivors in nearby rural counties (like Greene, Hale, Sumter, and Pickens). Unlike Webster County (where the Oats family lives) which is 79% white, these counties are in the southern “Black Belt” and are between 40-80% African American.

Ethel Giles, who also works with the Federation, says, “To our folks, as far as I know, I think [FEMA] did good.” She and Zippert say they have not seen racial discrimination in their area. Even so, they say resources are falling short.

Giles points to Ms. Thennie Jackson, a resident of Tishabee road in Greene County, as an example of recovery. A tornado caved in half of Ms. Jackson's roof, as she and her family prayed inside and waited for it to pass. After weeks of appeals, Ms. Jackson has fortunately gotten funds from FEMA to repair her home. But now she faces a new challenge – she has to replace all of her destroyed furniture and appliances, and a washing machine costs a whole month’s income.

Back in Webster County, Mississippi, Cherraye Oats says about 20 families have reached out to her looking for assistance because they are still displaced. Some are living in cars or staying on their families’ couches. “A lot of people got assistance,” she says, “But [it] is really not enough to get them back on their feet.” Ms. Jackson in May 2011, outside of her home on Tishabee road. She had been spending sleepless nights in her daughter's home and spending days on her porch, "the sturdiest place in the house." Photo by Ada McMahon.

Ms. Jackson in May 2011, outside of her home on Tishabee road. She had been spending sleepless nights in her daughter's home and spending days on her porch, "the sturdiest place in the house." Photo by Ada McMahon.

The tornadoes hit a region – the Black Belt specifically and the South generally – where many communities were already struggling with entrenched poverty, racism, poor schooling and other social and racial inequities that date back to the slavery era.

Even a recovery absent of outright discrimination can exacerbate these injustices, as it is poor communities who have the hardest time making up the gap between government assistance and the true cost of the damage.

“The storm added more variables to an already critical situation," says Glenda Williams, a Tuscaloosa-based community organizer with the Southwest Alabama Association of Rural and Minority Women. "What are people going to do when winter comes?… I hope that this storm does not create another level of impoverished people that are not in the loop, pushing people over the edge…” Williams says that in rural areas around Tuscaloosa, many are still homeless and staying with family or in their cars.

Monique Harden, a New Orleans-based attorney with Advocates for Environmental Human Rights, also worries about long term impacts; “The more prolonged a family’s displacement is, the more entrenched it will be that the children, and the children of those children, will not see the same level of progress as the parents. You can have this downward spiral...

“We think about a tornado, ‘Well, it happened in the spring of 2011.’ But [the impact] can go on into 2020, 2050.”[2]

******

Like many Gulf Coast advocates, Harden became an expert in disaster recovery after Hurricane Katrina.

She says Katrina exposed how policies made in the name of “recovery” often serve the needs of politicians and private business interests, while harming “folks that are lower on the socioeconomic strata.”

For example, Louisiana’s Road Home program used a grant formula that discriminated against African American homeowners. Then, Harden explains, “low grant payouts would induce applicants to sell their property to the state, which then resold the property to real estate developers.” In Mississippi, Governor Haley Barbour attempted to direct $600 million in housing grants towards expanding a state port. Those grants were originally required to build homes for people with low and moderate incomes, but the Department of Housing and Urban Development waived that requirement in the name of speedy recovery.

Meanwhile, survivors of Katrina are still living in storm-damaged homes, are still pushing the government for promised resources, and are still displaced and scattered across the U.S.

Ethel Giles unloads donated food at the Federation of Southern Cooperatives' center in Epes, Alabama, May 2011. Photo by Ada McMahon.

Ethel Giles unloads donated food at the Federation of Southern Cooperatives' center in Epes, Alabama, May 2011. Photo by Ada McMahon.

******

The story of how disaster recovery unfolds, and often perpetuates social injustices, has implications across the U.S. and the world.

That’s because disasters caused by extreme weather are on the rise nationally and globally. 2010 was a record-setting year of national emergencies in the U.S. That is, until 2011 surpassed it with 89 national emergencies (so far) – including midwest and southern tornado outbreaks, wildfires and drought in Texas, the flooding of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, Hurricane Irene, and record snowfall in parts of the northeast. Less than a month after the southern tornado outbreak, a mile-wide tornado swept through Joplin, Missouri and killed 116 people. Scientists link extreme weather to a global climate crisis caused by man-made carbon pollution, and warn that the unprecedented disasters of 2011 are the “new normal.”

Despite the growing need, funding for disaster preparedness, response, and recovery is far from secure, thanks to the struggling economy and right-wing hostility towards government spending on basic public services. In a debate in June, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney argued for privatizing disaster response, saying it is “immoral” for the U.S. government to perform services that add to the budget deficit.

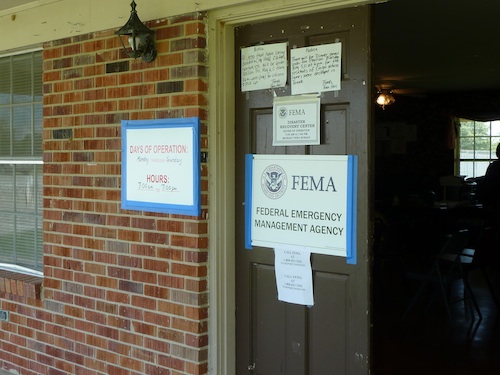

Debates like this matter, because disaster response is entirely at the discretion of the government – disaster survivors don’t have rights to recovery under U.S. law. A FEMA center set up in the Geiger, Alabama town hall after the April 2011 tornadoes. Photo by Ada McMahon.

A FEMA center set up in the Geiger, Alabama town hall after the April 2011 tornadoes. Photo by Ada McMahon.

Monique Harden explains that under the Stafford Act, “Once a national disaster is declared by the President, all action by federal agencies is entirely discretionary. People affected have no right to get assistance… As nightmarish and anguishing and horrible as [Katrina recovery] was – it was never illegal. Dozens of lawsuits were all dismissed…

“One thing Americans are waking up to is how little protection they have in the wake of a disaster,” she says.

That is why Harden's group, Advocates for Environmental Human Rights, is pushing for the federal government to adopt the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, a human rights-based standard for ensuring the recovery of people displaced by a disaster.

******

For some in the tornado disaster zone, the government’s lack of protection for ordinary people, especially in low-income communities of color, is no surprise. It’s part of why people like Cherraye Oats, John Zippert, Ethel Giles, and Glenda Williams became community organizers in the first place.

With recovery far from over, Cherraye Oats is looking into legal options for her displaced Mississippi neighbors; Ethel Giles is putting together a Thanksgiving Dinner so no one has to go hungry on the holiday; and the Federation of Southern Co-operatives is organizing “self help housing groups,” in which neighbors pool resources and help rebuild each others’ homes.

While they advocate and push for a just recovery – these communities will continue to do what they can to provide for themselves.

************************************************

Footnotes

[1] I could not reach Alford directly for comment. The Director of Webster County Emergency Management Agency (EMA), Barry Rushing, told me he hadn’t heard anything about the incident, and that Alford is not EMA personnel. He said Alford may be a member of the local fire department, which helped with the relief effort. Someone at the firehouse confirmed that Alford is a member. Cherraye Oats says that in fact she did bring the incident to Rushing in a meeting, and he “blew us off.” She also contends that Rushing and Alford are friends.

Meanwhile, Oats says this is not the first, or last, run-in they’ve had with the racism and misconduct of local authorities. In August, at her sister’s 14th birthday party, Courtney says she was arrested by local police for “disorderly conduct” after a police officer called her mother a “black b****” and threatened to use a taser on her sister. According to Courtney, the same police office confronted her earlier that day for putting up posters for a community event that celebrated healthy food and racial healing, saying “Don’t bring that here” and “I’ll catch you later on”. [Source: http://civileats.com/2011/09/21/arrest-does-not-stop-food-and-freedom-ride/ and a written account by Courtney Oats].

[2] Harden cites a passage from a U.S. State Department report on internal displacement, “Prolonged displacement typically disrupts or reverses progress made in schooling, healthcare, food production, sanitation systems, infrastructure improvements, local governance, and other sectors fundamental to economic and social development…” Download the report here.

Top photo: Aftermath from a tornado in Greene County, Alabama. May 2011. Photo by Ada McMahon

Related post: After tornadoes, rural disaster area faces relief challenges (Part One)

************************************************

Ada McMahon is a Media Fellow at Bridge The Gulf (www.BridgeTheGulfProject.org), a community journalism project for Gulf Coast communities working towards justice and sustainability. She previously worked as a blogger and online organizer at Green For All, a national non-profit that fights pollution and poverty through "an inclusive green economy". She is from Cambridge, Massachusetts, and currently lives in New Orleans, Louisiana.