Learning the Price of Defiance in Pascagoula

By Alda Talley. Original published on On This Creole Coast and reprinted on The Oyster Knife. September 30, 2012, was the 50th anniversary of the entry of James Meredith into Ole Miss in 1962, thereby “integrating” the flagship university in my home state of Mississippi. Though noted in many newspapers and news media, the coverage had a sameness about it, usually using Charles Eagles’ 2009 book, The Price of Defiance: James Meredith and the Integration of Ole Miss as a source and focus.

By Alda Talley. Original published on On This Creole Coast and reprinted on The Oyster Knife. September 30, 2012, was the 50th anniversary of the entry of James Meredith into Ole Miss in 1962, thereby “integrating” the flagship university in my home state of Mississippi. Though noted in many newspapers and news media, the coverage had a sameness about it, usually using Charles Eagles’ 2009 book, The Price of Defiance: James Meredith and the Integration of Ole Miss as a source and focus.

Not usually mentioned is the source of the phrase “the price of defiance”, nor the three important players from Pascagoula, Mississippi, my home town, in the struggle for integration of Ole Miss: Karl Wiesenburg, Ira Harkey, and Albin Krebs. Mr. Eagles does include them in his book. I had earlier learned of their role while researching my own racial and social history as a daughter of Pascagoula and the Creole Coast. Besides their being from Pascagoula, I’ve also discovered ties to my family, my church, and my school that make me proud.

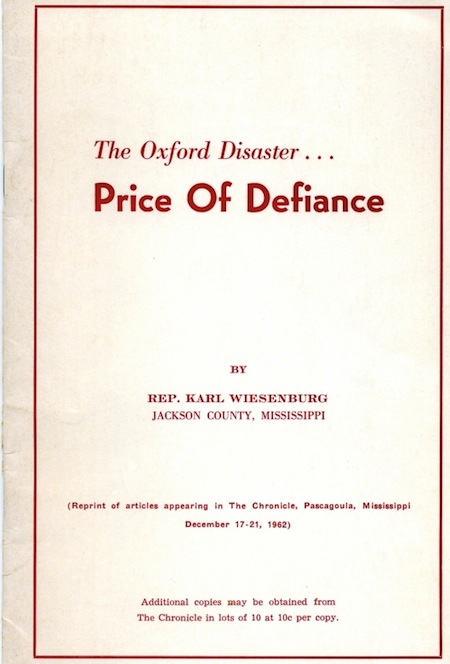

Karl Wiesenburg (1911-1990) was a self-taught attorney — he never finished high school, and didn’t attend college or law school — and the State Representative to the Mississippi Legislature from Pascagoula during the time Mr. Meredith arrived at Ole Miss. It was he who wrote a series of articles for The Chronicle, the local newspaper, in 1962, setting forth the “price of defiance” of the federal government by the state. In measured, legal terms, Mr. Wiesenburg laid out his case for complying with the order to integrate Ole Miss, and the ramifications of continued non-compliance. In Jackson, his was an often lone voice in the legislature against segregation. At times, Rep. Joseph Wroten of Greenville joined him in his brave and very dangerous stand.

Robert F. Kennedy, then the U. S. Attorney General, wrote of Mr. Wiesenburg at the time, “It is all well for we in the North to talk about these matters. That takes no courage at all. But people such as…Mr. Wiesenburg are the ones who really carry the banner.”

Cover of “The Oxford Disaster…Price of Defiance”

My momma was Mr. Wiesenburg’s legal secretary before I was born — I don’t know exactly when. I do remember him as her attorney, and going to his office with her when I was a little girl. It was easy to see the great devotion and respect they had for each other. I also remember seeing Mr. Wiesenburg every Sunday at Mass with his wife and family, and around the Catholic school we all attended. His niece was, and remains, my dearest childhood friend and ally. I still crab next to his former home on Krebs Lake.

The decision to print Mr. Wiesenburg’s articles in The Chronicle was made by Ira Harkey (1918-2006), the editor and publisher of the Pascagoula newspaper at the time. Harkey was from New Orleans, and a graduate of Tulane. He reprinted the articles in booklet form so that they might gain more readers. This booklet was titled “The Oxford Disaster….Price of Defiance”.

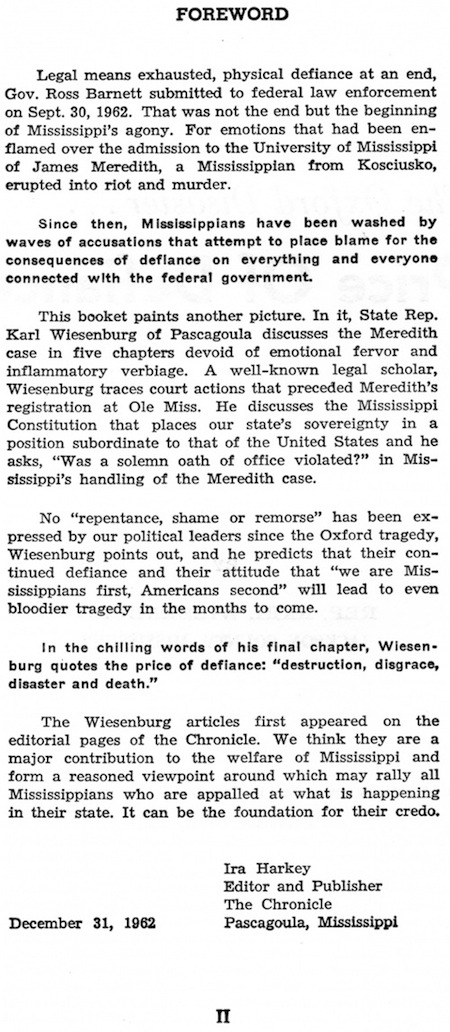

Inside front cover of “The Oxford Disaster…Price of Defiance”

Inside front cover of “The Oxford Disaster…Price of Defiance”

In 1963 Ira Harkey was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Writing “for his courageous editorials devoted to the processes of law and reason during the integration crisis in Mississippi in 1962.” He later wrote The Smell of Burning Crosses: A White Integrationist Editor in Mississippi, about this period of his life in Pascagoula and the cost of his own defiance, which included, besides the cross burning at his home and at the newspaper, death threats, a boycott of the paper, and social shunning in the community.

Albin Krebs (1929-2002) was born in Pascagoula and went to Catholic school there. While still a young man, he walked across the parking lot next to our school and church to work under Ira Harkey at The Chronicle. He set off for college at Ole Miss, and became the editor of the university’s newspaper, The Mississippian, in the spring semester of 1950. He promptly set about writing editorials on the important issues of his day, taking very unpopular stands against the injustices he saw, including the activities of Senator McCarthy, the banning of books, and the evils of segregation.

In October of 1950, twelve years before James Meredith came to campus, Krebs wrote and published an editorial advocating the integration of the Ole Miss Law School, sparking riots, the burning of crosses outside his dorm room, efforts to have him expelled, and denunciations of him from the governor and the head of the university, on down through the state legislature, and from newspaper editors across the South.

Mr. Wiesenburg was his attorney during this period, and filed a successful suit for defamation, among other legal actions. Hodding Carter praised him in an editorial in the Delta Democrat Times. Krebs was a welcomed speaker at the first NAACP national convention to be held in the South, in Atlanta, along with Thurgood Marshall. His editorials in The Mississippian continued to resound in the debates over the integration of higher education in Mississippi and elsewhere, and were often recalled during the difficult days of 1962.

Although I went to school with the nieces and nephews of Albin Krebs, was taught history by one of them in Catholic school, and was a not-too-distant relative, his story and his importance in the life and history of my state was unknown to me until a few years ago.

Learning the stories of these three men — Karl Wiesenburg, Ira Harkey, and Albin Krebs — make me understand my own life growing up in Pascagoula, and shed light on how I came to be who I am and have the values I do. We shared in that remnant of Creole culture that remains in Pascagoula, a remnant of the French-speaking Catholic folks of mixed race who populated the town from its beginnings in the early 1700’s. (This same Creole culture is what we associate with New Orleans of the time; in fact, it was present all along the Gulf Coast from west of New Orleans to Mobile, and remains so to varying degrees today.)

Mr. Wiesenburg and Mr. Krebs, both Catholic, must have experienced the prejudice aimed at Catholics by Protestants and the KKK in their time. (Even today, many people don’t realize that the KKK hated the “papist” Catholics and aimed their violently Anglo Protestant attention at them; though this does not compare to the breadth, depth, or longevity of their deadly hatred for African Americans.) I experienced a parallel segregation of a different sort because of such prejudice — the segregation between Catholics and Protestants.

The church and school Mr. Wiesenburg and Mr. Krebs attended, Our Lady of Victories, wasn’t the only Catholic church and school in Pascagoula; there was also St. Peter’s Catholic church and grade school, in my neighborhood. St. Peter’s parish had been formed in the 1870’s, during the re-segregation of the South after Reconstruction, when Pascagoula, New Orleans, and other Creole towns along the Coast were forcibly segregated by the Anglos. Many, if not most, of St. Peter’s parishioners were decendants of Free People of Color who had lived in Pascagoula and along the Creole Coast since the 1700’s. There are many ties of blood kinship between members of the two parishes — including many in my family. In my time in Pascagoula, our common Catholic faith joined us together more than our skin colors separated us. Students from St. Peter’s grade school often continued their education at OLV high school, and had done so for many decades.

Although Pascagoula had its share of the horrors of racism in Mississippi, I was largely shielded from its vitriol by virtue of being Catholic in a Creole culture. The kind of overt, violent, hateful racist speech and actions that so permeated Mississippi were not tolerated in my home, my church, or my school.

(None of this is to say that I didn’t imbibe racism while growing up in the South. I don’t believe that’s avoidable for white folks. We all are afforded privilege because of our perceived race. Nor do I mean to imply that I do not continue to struggle to “unlearn” my racism and overcome it in my thoughts and actions, nor to continue to try to see and understand the ways that it permeates and is institutionalized in the world we all inhabit. Uncovering the truth of the part of the world I grew up in and remained ignorant of is part of my work and my struggle; learning the stories of men like Karl Wiesenburg, Ira Harkey, and Albin Krebs is both part of that work, and part of its reward.)

Even though as a child I was unaware of the actions of these men, I could feel their ramifications and sense both the respect and the hatred they inspired in my small town. I was not privy to the conversations of the adults about the cross burnings; but I was very aware of not being left free to visit the homes or play in the yards of the white folks in my neighborhood who didn’t go to OLV. While racist speech and comments were commonly heard as I shopped or went about other business in town with my momma, she never failed to steer me away and out of earshot, always angrily going on about the ignorance and, yes, trashiness, of the folks talking that way.

There were very few books in my home growing up that weren’t lives of the saints or the encyclopedia. This was pre-Vatican II, so even the big showy Bible we had was mostly for recording family genealogy, and not for reading. One exception that has always stood out in my memory was the copy of The Smell of Burning Crosses that was on a small shelf in the laundry room, me and my mother’s domain. I never read it; I vaguely remember being told by Momma that it wasn’t for children. I always wondered why it was there. I always pondered what the title meant as I stood facing it over the ironing board most mornings, pressing the pleats into my Catholic school uniform.

Now I know.

~~~~~~~

To learn more:

“An Interview With Karl Wiesenburg” Interviewed by H. T. Holmes, August 9, 1976, Pascagoula Mississippi. Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., Robert Kennedy and His Times, 2002.

Charles W. Eagles, The Price of Defiance: James Meredith and the Integration of Ole Miss, 2009

Karl Wiesenburg, “The Oxford Disaster…Price of Defiance”, 1962.

Ira Harkey, The Smell of Burning Crosses, 1967; republished in 2006.

“Albin Krebs, 73, Obituary Writer” obituary in the New York Times. June 4, 2002.

(There is a wealth of information available online — enter any of the names mentioned in the essay in your favorite search engine. Especially good are university and state historical archive websites.

Abebooks.com is a good source for out-of-print items; that’s where I obtained my copy of “The Oxford Disaster…Price of Defiance”.)