Jordan Frazier, Killed by Baton Rouge Police, Was Unarmed, Witness Says

By Daryl Khan and Clarissa Sosin

This story originally appeared on Juvenile Justice Information Exchange.

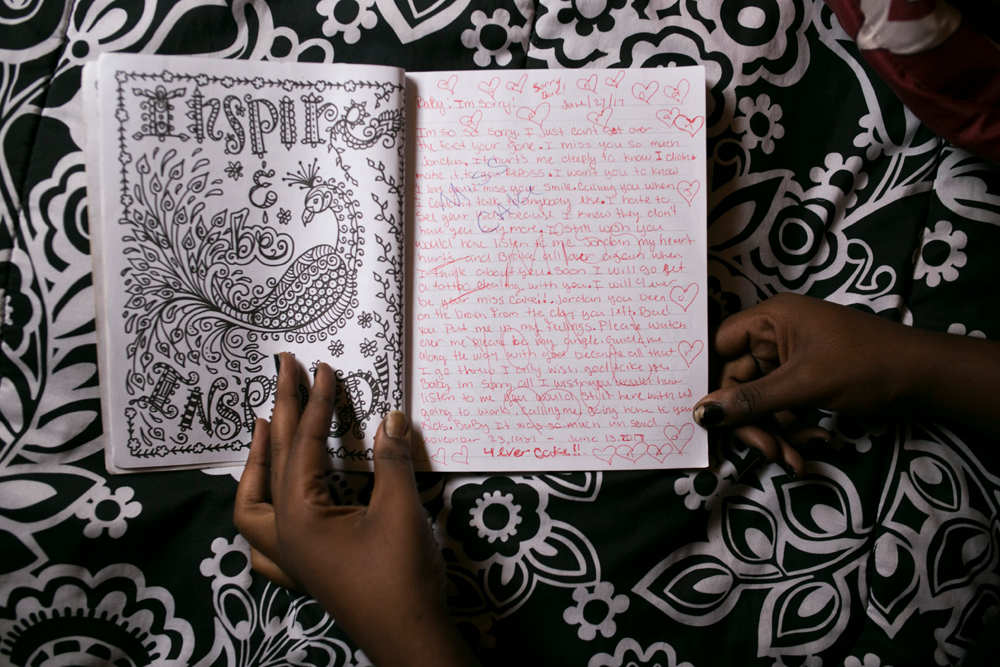

BATON ROUGE, La. — The young woman sat on a mattress in the middle of the floor of her bedroom in North Baton Rouge. Open in front of her was the diary she started after her friend, Jordan Frazier, was shot and killed by a Baton Rouge Police officer during a traffic stop. The entry was dated June 27, 2017, just more than a week after his death.

“I still wish you would have listen to me Jordan my heart hurts and brake all over again when I think about you,” she wrote in a bubbly red print. Around the edges of the page she’d drawn hearts with one letter in each spelling out his name. Across the entry she’d scrawled in big red letters “I MISS YOU BAE.” Next to that she’d written in blue ink “MISS CAKE,” her nickname for him.

“I hate to see your kids because I know they don’t have you anymore,” she wrote.

She compared herself to Jiminy Cricket from Pinocchio, she said, a benevolent force looking after Frazier’s children, who live with their mother nearby.

“I feel like I owe them that,” she said. “That’s all I can do.”

The woman had been with Frazier the night he was killed. She was driving the car that was pulled over. Until now, she’s kept quiet about that night. At first, she had been too scared to come forward to the public with her version of what happened. But, a year later, when the officer who killed her friend almost shot and killed another young black man, Raheem Howard, under similar circumstances, she realized she needed to set the record straight. But, she wanted to keep her identity hidden because she’s worried about her safety, she said. She’d received death threats. She doesn’t know from whom.

According to authorities, Frazier pointed a large handgun at Officer Yuseff Hamadeh and his trainee partner. Hamadeh fired the fatal shots before Frazier could shoot them. At the time, the BRPD told local media that there was a driver in the car, but they never identified who it was; the department has refused to release the police report of the incident.

The gun the BRPD showed the public and local press was not Frazier’s and was not on his person or in the car that night, the woman who drove the car said. She doesn’t know whose it was or where it came from, but knows it wasn’t his. He wasn’t armed.

Officers spoke to her after the incident, but it is unclear whether her name is in the police report from that night. The police department has refused a public records request, as has the Louisiana State Police, which exonerated the officer in the shooting. Both agencies have cited the state’s exemption from the law, saying that the case remains under investigation. All the agencies involved in investigating the shooting have declined to comment for this story.

‘I’m about to go, Bae’

The woman and Frazier had been out for a drive on June 13, 2017 when the BRPD squad car did a U-turn and began to follow them. She figured the officer was pulling her over to give her a ticket for her headlight. There was a loose wire in her headlight, and bumps in the road, like the one she’d just hit on South Acadian Thruway, made it cut in and out. She had been meaning to get it fixed.

But her friend sitting in the passenger seat next to her thought otherwise. Frazier was panicking. He was cursing at her, something he had never done before.

“He used some foul words,” she said. He told her: “What the fuck you did to make them come behind us like that?”

The young woman had never seen him like this. She tried to calm him down and explained that the police weren’t going to bother with him. She was the driver. They were only going to run her driver’s license. But Frazier wasn’t listening to reason. He had a criminal record and ecstasy in his pockets. He was out on bail for trying to sell the drug following an arrest in March.

Then, according to her, the officers inside the car turned on their lights and siren, indicating she had to pull over. She did. Two officers climbed out of the car.

Frazier looked at her, an intense look in his eye. He kissed her on the hand, and then kissed her on the neck.

“I’m about to go, Bae,” she remembered him saying.

“No, don’t go nowhere,” she responded.

He didn’t listen to her. What happened next she’s played out in her mind many times.

Frazier opened the car door and bolted. Within seconds shots rang out, she said. Frazier had barely passed the front bumper when he tumbled to the ground. He fell on his stomach. Then, he managed to turn over and raise his hands, a motion pleading for the officer to stop.

She screamed. The other officer — a trainee at the time who did not fire the shots and remains unidentified by the BRPD — leaned into the car with his gun drawn and pointed it at her head.

A diary entry about Jordan Frazier written by the woman who was driving the car the night he was killed, photo by Clarissa Sosin

A look of fear crossed over her face as she remembered what he shouted at her.

“Shut the fuck up before I shoot you,” he yelled at her. “They really treated me like I was the one who did something,” she said.

Neither officer asked her for her license or registration, she said. And she never received a ticket. Instead, they started pouring over the car to see what they could find. More officers arrived, some in plainclothes, some uniformed. She was handcuffed and shoved in the back of a BRPD squad car, Frazier’s body no longer in sight. She sat there for hours while investigators remained at the scene.

Eventually officers took her to a nearby gas station to use the bathroom, then drove her to police headquarters where she was taken up to an interrogation room. She was never formally arrested, but was detained and questioned, she said. The interrogation didn’t make sense to her. Over the next few hours, she was puzzled by one line of questioning that kept coming up. It was about a gun. They insisted Frazier had it. Where was he keeping it? Where had he hidden it? What was he doing with it?

She had spent the whole afternoon with Frazier, she told the officers. He never had a gun that day.

The interrogation lasted until dawn, when she was finally released.

The young woman said she was confused by the news accounts after the shooting. They reported that the police officer had shot Frazier after he pulled out a gun and pointed it at the officer. She knew that wasn’t right. Frazier didn’t have a gun when he scrambled out of the car.

She was too shaken to come forward — until now. She eventually talked to her uncle about it in confidence. Aside from him, the only two people she talked to identified themselves as investigators. She doesn’t know what agency they were from, but the Baton Rouge Police Department and the state police have a memorandum of understanding that all shootings and fatalities will be investigated by the state police. They chatted with her on the sidewalk near her home for about 10 to 15 minutes, she said. They asked her a series of questions about what happened the night Hamadeh fatally shot Frazier.

They never asked her whether or not Frazier had a gun that night.

News reports said that Frazier had a distinctive handgun on him: a Ruger .22 Mark II. According to state police, it was stolen from nearby Ascension Parish. The woman said she couldn’t see Frazier’s body after they cuffed her and put her in the back of a squad car. She doesn’t know how it got there.

‘Even in death’

The Fraziers were upset, as any parent would be upon hearing the news that their child had been killed. But initially they were at peace with it. Jordan Frazier, their youngest child, had pointed a gun at a Baton Rouge Police officer during a traffic stop so the officer shot him, they were told by the state police.

They didn’t raise their son to act that way with law enforcement. His father, Henry, fought in Vietnam and served in NATO. His mother, Helen, worked in the local school system. It was a strict household, a “yes ma’am, no sir” household, the parents explained. They both had a respect for authority and tried to instil that in their children. So although they were despondent at the loss of their 35-year-old son, they thought he got what he deserved.

“I would never condone our son pointing a gun at an officer, and I was ready to settle for that, that Wednesday morning when we were briefed on what happened,” said Henry, sitting on a wooden chair in his living room a year after his son had been killed.

His wife, Helen, sat across the living room, a ladder shelf filled with framed cheerful family photos behind her. It had been more than a year since their son had been killed.

“If we believed in them and thought that what they were doing was right, we were behind them 100%. But if they were wrong, they got no support from mommy and daddy. And that’s just the way they were raised,” she said agreeing with her husband. “Even in death.”

Although the Fraziers’ home is just 20 miles north in the small town of Zachary, it seems a world apart from the streets of North Baton Rouge where their son died.

Their house sits on a large plot of land on a road that feels rural despite being so close to the state capital. Trees dot the horizon and a well-kept lawn separates them from their neighbors. Inside the house is impeccably clean. Family photos are scattered throughout and a get well poster for Henry, handmade by a grandchild, hangs on the wall.

Mementos from Jordan Frazier’s youth hang on the walls of the Frazier house in Zachary, La., photo by Clarissa Sosin

When they were told by investigators that their son had a gun, the Fraziers said they thought that chapter of their life was finished. The investigators had said that their son had been the passenger during a traffic stop and that he’d leaped out of the car and pulled a gun on Hamadeh and the trainee assigned to him that night. Hamadeh fired multiple shots in response. The case seemed straightforward to them and the shooting perfectly defensible.

“We thought it was over,” Henry said. “We made arrangements to have him buried.”

But two days later, when they were returning from finalizing the details for the funeral, they got a call.

“Those same state troopers called us, just like the barn was on fire,” Henry said.

Helen interrupted, finishing the thought: “Because they had a different story to tell.”

The state investigators were eager to talk to them, the Fraziers said, because they didn’t want them to hear about the coroner’s conclusions on the news. The report stated that their son had been shot in the back, not the front as they had originally been told.

“A police officer said that Jordan had pointed a gun, and that was the end of the story,” Helen said. “That was the end of the story, irrespectful of the fact that he received three bullets to his back and then you’re going to tell me that that’s the end of the story? It’s not the end of the story,” she said. “It’s just the beginning of the story.”

Henry twisted in his chair to try to illustrate the awkward mechanics of the second story the investigators told them. They explained that their son had pulled the gun out and twisted his body around to aim it at the officers, all while he ran in the opposite direction.

Hamadeh was investigated and cleared to go back to patrol just weeks later. Since then, Hamadeh’s reputation has gone through twists and turns. He is no longer on the force.

The Frazier case technically remains under investigation by East Baton Rouge District Attorney Hillar Moore III. But the Fraziers are skeptical of the investigation’s integrity. They fear the investigation into their son’s death has been buried. They’ve tried multiple times to get a copy of the coroner’s report but they have not been successful.

“Here we are, two citizens of this city, that should get the same respect as the police officers get, and are getting nothing. Nothing. It’s one-sided. It’s totally one-sided,” Henry said. “All we wanted was from an official source, ‘This is what happened.’”

They are still waiting.

‘All you have to do is change the names’

Nearly a year after Frazier’s killing, Hamadeh was involved in another shooting that shared a number of similarities with the Frazier incident. Except this time, the suspect, Raheem Howard, survived and fled the scene.

“If you would have put a gun on the ground in this young man’s case and a bullet in his back and you have the same thing,” Henry said, comparing Howard’s case to his son’s. “All you have to do is change the names. It’s the same story.”

The details of the incident are laid out in a civil suit filed for Howard by his lawyer Ronald Haley Jr. against the BRPD for excessive force.

Howard, 20 at the time, was driving his friends back from a job training at a nearby seafood restaurant when Hamadeh, while pulling him over, rammed his unmarked car into the back of Howard’s car in a residential neighborhood. Panicked, Howard jumped out of the car and ran.

Hamadeh chased after him. He pulled out his gun and fired at Howard, who disappeared into the neighborhood. Hamadeh put out a call over the radio saying that Howard shot at him first. A manhunt ensued. Howard ultimately turned himself in and during a “perp walk” vigorously maintained his innocence.

“I didn’t have no gun,” he said to local reporters, his voice quivering with fear. “They got the body camera, the dash camera. I didn’t do nothing but run.”

Howard asserted in his civil suit that during his interrogation, officers encouraged him to confess to shooting at Hamadeh. He said BRPD investigators kept telling him that they had everything on video. This turned out not to be true. Hamadeh’s body camera and his front dash camera were turned off at the time of the incident. But there was a police record: an audio recording from the rear dash camera, which had been pointed down.

While Howard sat in the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison facing a possible life sentence for attempted murder of a police officer, there was an outcry from witnesses in the neighborhood who said they only heard one gunshot. Residents and advocates pressured the BRPD to release any recordings of the incident.

When the audio was made public, Howard’s innocence was confirmed. There was only one gun shot in the recording — the one from Hamadeh’s gun. District Attorney Moore dropped the charges against Howard, saying there was not enough evidence to prosecute him. Moore has further promised to review all the cases Hamadeh was involved in. The district attorney’s office now doubts his credibility in court. So far there have been numerous criminal cases that Hamadeh investigated where the charges were either dropped or reduced.

In October 2018, BRPD Chief Murphy Paul fired the officer for lying about that day; he hadn’t told internal affairs investigators he’d crashed his patrol car into Howard’s car during the traffic stop that led to the chase, the shooting and the manhunt.

But after a hearing in front of the Baton Rouge Municipal Fire and Police Civil Service Board on Jan. 17, 2019, Hamadeh got his job back.

It was a 3-2 decision that broke along racial lines. The three white members of the board voted to reinstate Hamadeh. Shortly after the decision, he and Chief Paul negotiated terms for his resignation.

The decision horrified the Frazier and Howard families.

Hamadeh’s lawyer, Thomas “Tommy” Dewey of Dewey & Braud Law, acknowledged that the accusations against his client were serious but said his client deserved due process.

“What is getting lost in all this is that my client was cleared by Chief Paul for use of force. For the worst part of this, the accusations of force and the shooting, he was cleared. They conducted an investigation, internal affairs did, and they found that it was not sustained, that’s the language they used,” he said.

Dewey said Hamadeh now works in the private sector and that he declined both a request for an interview and to comment for this story.

Haley, Howard’s lawyer, wants the Department of Justice to re-investigate the case.

“Punishing bad cops is something they seem immune to,” he said of the BRPD and the state police. “That’s that blue wall, it’s more powerful than the one Trump is trying to build — that wall of silence is deafening.”

So far, no officer from the BRPD will say there is probable cause to charge Hamadeh. If there is no police officer who goes on the record and testifies to that before a grand jury, the district attorney won’t charge Hamadeh with anything related to the Howard case. The Police Officers Bill of Rights ties the district attorney’s hands. He can’t use anything that was presented in Hamadeh’s termination hearing in a grand jury proceeding, Haley said. And unless new information comes up in the Frazier case, he won’t indict him for that either.

Myra Richardson, 20, an activist for police reform and a youth leader who participated in the Dialogue on Race and Policing last year, said there are multiple obstacles in the way of police reform and proper community oversight of the police. The Civil Service Board that gave Hamadeh his job back, made up of people appointed by the mayor, City Council and the police and fire departments, needs to also have representatives appointed by the community, she said.

“When we talk about, like, what are the systemic problems, it’s like the board is systematically being comprised in a specific way that doesn’t allow for justice,” Richardson said.

Richardson said that in an ideal world, Baton Rouge would establish a civilian oversight committee, like the Independent Police Monitor in New Orleans or the Civilian Complaint Review Board in New York City, but she said she doesn’t think it is politically feasible.

In May 2017, the BRPD Union came out against more civilian oversight saying the Civil Service Board was enough.

Where the wind blows

The response to Hamadeh’s actions revealed how ultimately the only agency holding the BRPD accountable for its excesses is the BRPD itself — creating what critics and the families of victims say is a conflict of interest.

The independent agencies that are supposed to scrutinize the BRPD for its excesses are not holding the department accountable, victims say. After an officer-involved shooting, the district attorney relies on the findings of the BRPD and the state police. The district attorney’s investigators are trained for case management — for example, making sure witnesses show up to court on time. They are not trained to vigorously investigate complicated criminal cases, defense attorneys familiar with the office said. If there were a more rigorous and independent review of police abuse, critics of the police department and family said, then Hamadeh would not have been back with the Street Crime Unit in a position to shoot and possibly kill Howard, or anyone else again.

Carl Dunn, a member of the BRPD for three decades, says the Louisiana State Police and the district attorney’s office work too closely with the department to be fair and objective. He is currently the police chief in Baker, the small town just to the north of Baton Rouge. He worked the streets of Baton Rouge as a patrol officer and the hallways of headquarters as an administrator.

“I wouldn’t say it’s a formal ‘We’re going to get together and cover this up,’” Dunn said. “I wouldn’t say that because that’s not what it takes. It takes their being in unison to see which way the wind is blowing on it and everybody falling in line. You don’t have to sit down and conspire a lot of times. I just want to know your way of thinking, and if we work together every day, that’s the first thing you’re going to learn.”

Dunn left the BRPD because he thought the department was encouraging a culture of excessive force instead of trying to rein it in. During his time as an administrator, he helped update the BRPD’s policy book, known as the “Blue Book.” If they followed just 50% of the policies in the updated book, instances of excessive force would be far less rampant, he said. But they don’t, he said.

Over the years the BRPD has done nothing to discourage excessive force because it’s not investigated rigorously by the department, Dunn said.

Even when it is, there are still cases such as Corp. Robert Moruzzi, a BRPD officer who was involved in two federal lawsuits accusing him of excessive force. He was fired in 2009 for his involvement in a downtown fight outside a bar in which he threatened to kill the manager, but appealed to get his job back. He was charged with simple battery, aggravated assault, simple assault, disturbing the peace by intoxication and misdemeanor theft but the charges were dropped in 2010. The next day he was back on the force after reaching an agreement with Jeff Leduff, the police chief at the time.

Then, in 2013, Moruzzi was accused of repeatedly shocking Jed Bricker with a Taser stun gun. Bricker sued him in federal court but the case was dismissed. In 2014, Moruzzi was accused of calling Brett Percle a “jack-o-lantern” after he kicked Percle’s head against the curb, knocking out teeth. The court found that Moruzzi had used excessive force and awarded Percle $51,412.

Moruzzi remains on the force today. On Jan. 17, 2019, he sat on the civil service board that determined that Hamadeh should get his job back.

‘I was just fighting for survival’

Tanisha Howard had never heard the name Jordan Frazier. It wasn’t until her son, Raheem, had an encounter with the same officer who killed Frazier that she learned the details of the case. After her son’s ordeal — being shot at, subjected to a manhunt, accused of attempted murder of a police officer and sitting in prison — she realized how lucky her son was to be alive.

She read up on the case and, like Frazier’s parents, was startled by the similarities. In fact, in another unexpected connection, a former colleague told her that she used to work at the same school where Frazier’s mother was a secretary. Now, after what has come out around her son’s case, she questions the integrity of the investigation into Frazier’s death.

“They didn’t give it as much attention that they should have,” she said about the media coverage of Frazier’s death. “You knew something about the report wasn’t right. And it was a young black man — you think they care?”

At first Howard thought her son had met the same fate as Frazier after his encounter with Hamadeh. That day she received a frantic phone call — she can’t remember from who — that her son had been killed by the BRPD. The person told her they thought her son’s body was by the church. She needed to come identify it.

“Our life changed. Not only Raheem’s life changed, but my life also changed. To come home from work to get a call that says your son just got killed by police officers,” she said. “Can you imagine, as a mother, what I’ve been through?”

Raheem is still haunted by the ordeal. He’s had to deal with financial problems, like the loss of his car, and missed job opportunities. And when people look his name up, they see it associated with the attempted murder of a police officer. But it’s the psychological toll that has been the hardest. When he reflects both on running for his life and sitting in a cell thinking about a life sentence behind bars, he holds back tears.

“I was just fighting for survival, I really don’t like talking about it,” he said. “Nobody wants to sit down and see what I’m going through.”

He was released from prison in October and has been trying to get his life back on track since. He even moved to Jacksonville, Fla., to start over. But he is angry at losing two months of his life on a made-up charge. Now, as he works on his civil suit, he has one mission.

“I want justice — and when I mean justice, I should see [Hamadeh] the same way I was on the news. I should be seeing him with his head down on the news knowing that I’ll be going to every court date to testify against him because he tried to kill me,” Howard said. He worries that if Hamadeh ever gets hired again as law enforcement, he’ll try to kill someone else.

Haley, Howard’s lawyer, who also worked briefly on the Frazier case, said he thinks the ordeal that the BRPD put Howard through makes taking a second look at Frazier’s death all the more urgent. If the district attorney is dropping cases Hamadeh was involved in because they doubt his credibility, then it means they need to return to the Frazier case as well, he said.

“What happened to Raheem — and what we now know about what happened to him — it makes everything else possible,” Haley said. “If y’all are willing to do all that for a mistake where no one gets hurt, what are you going to make up if you accidentally kill somebody? Or intentionally kill somebody? Ask yourself: What would that cover-up look like?”

‘I want to reassure the citizens of Baton Rouge’

The Frazier house in Zachary is a warehouse of Jordan’s mementos. There are the ones that commemorate his triumphs. Team photos from his years of high school sports hang on the walls of the game room across from a bureau crammed with trophies. Then there other mementos — an ornament with his photo that says “First Christmas in Heaven,” and a stack of old newspapers filled with articles related to his case.

One of the articles describes the ceremony during which Hamadeh was awarded a Medal of Valor for killing their son.

Helen, his mother, had always supported the police. She had faith in the system. But the investigation into her son’s death hardened her. After hearing different stories from the state police, and then being ignored for more than a year by the district attorney’s office, she said she doesn’t believe in the system anymore.

“To me there’s just no truth. We don’t know. We can’t get anyone to talk to us. We only know what we know: We’ve lost our son,” she said.

What happened to her son is a harsh reminder of where they live, she said. This is the deep South, she reminded visitors, where the vestiges of Jim Crow can be seen everywhere from the ubiquitous Confederate battle flags hanging from porches or slapped onto car bumpers to law enforcement’s treatment of black residents.

“That’s the consensus here. That if you’re a black young man and you get stopped by a police officer you run. Ours ended up dead,” she said.

After the second high-profile shooting, involving Hamadeh and Raheem Howard, Chief Paul wrote a public letter to the citizens of Baton Rouge.

“As your Chief, I wholeheartedly believe in transparency. I have worked hard to gain the public’s trust since I took the oath of office in January of this year,” he wrote. “I want to reassure the citizens of Baton Rouge that our Baton Rouge Police Officers are conducting a thorough investigation into this incident.”

But Helen and Henry Frazier said they, too, were assured of a thorough and independent investigation. But all they have heard were a series of stories from investigators, each more unbelievable than the last.

“Shoot first and ask questions later,” Helen said of the police department that killed her son. “You know, all I see, all I see they see is that my son is just another dead nigger. I’m sorry, but that’s all they see. It’s just another dead nigger. That is it.”

The Fraziers said they feel as though black residents and police are held to different standards in Baton Rouge.

“The police should have to face the same laws that we face,” Henry said.

Growing up, Henry experienced firsthand what it was like to live under two standards. As a teenager, he risked his life fighting for civil rights. He integrated the first segregated public school in Southern Louisiana. The memories still trouble him. He doesn’t like to talk about it. Now, as he nears the end of his life, he finds himself, almost 60 years later, embroiled in another civil rights battle.