Football Player Sues Southern Miss Alleging Violation of Disability Rights Law

NCAA Division I football player Deven Hammond was born with only one kidney, but that never slowed him down — until he tried to play for the University of Southern Mississippi.

Hammond played both quarterback and defensive back in high school, earning a trip to the Offense-Defense Bowl along with other top high school seniors from across the country. Highly recruited, he played a year at Louisiana State University (LSU) before Coach Dan Disch convinced him to transfer to University of Southern Mississippi (USM) with the promise of a full scholarship if he made second string or better after one semester.

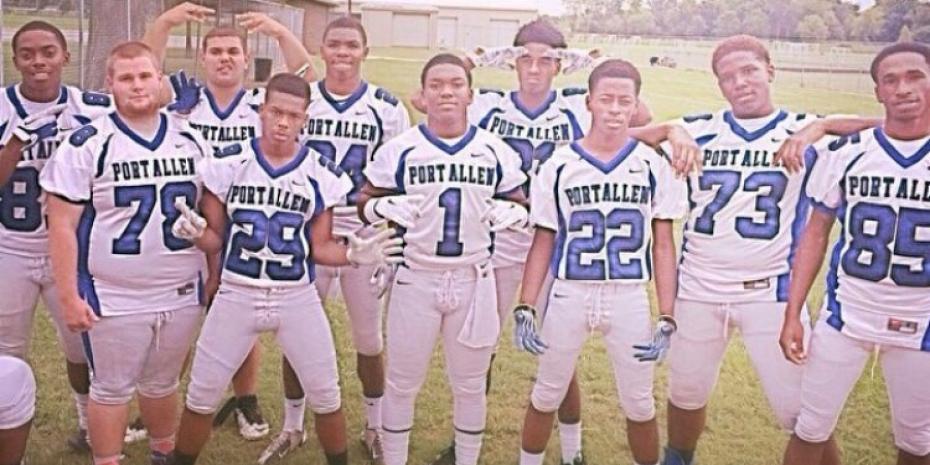

(Above: Hammond, center, with teammates from Port Allen High School. Photo provided by Deven Hammond)

Early last June he made the move from Baton Rouge to Hattiesburg, ready for summer practices. He easily passed an athletic physical at the USM health center, where he disclosed — as he said he always does — that he has only one kidney.

But a few weeks later, when he mentioned to USM head athletic trainer Todd McCall that he had only one kidney, McCall immediately pulled him from practice. Hammond said he wasn’t worried about the extra documentation and provided the school with a letter from his nephrologist attesting that he was fit to play.

But USM wouldn’t budge. He was still barred from practicing.

“Once we got to a point where the doctor didn’t clear me that’s when it kind of hit, like wait a minute, somebody pinch me, is this real?” said Hammond, adding that he’s been monitored as a precaution since birth, but never needed kidney-related treatment.

After several attempts to convince the school to accept his doctor’s approval — and the approval of its own health center — Hammond has filed a lawsuit against the University of Southern Mississippi football program, Coach Dan Disch and a yet-to-be-identified member of the USM athletic program, alleging they violated the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Rehabilitation Act (Rehab Act).

In the suit, which was filed Wednesday in Baton Rouge federal court, Hammond alleges that USM violated Hammond’s rights by not allowing him to play even though having one kidney does not medically prohibit him from playing.

Hammond also alleges that someone at USM shared his private medical information without his permission, a violation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA).

“I just don’t want anyone else to have to deal with a situation like this, whether it’s at this university or any other university,” said Hammond, who according to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) is one of an estimated 1,000 babies born each year with only one kidney.

Hammond grew up in Brusly, LA, just south of Baton Rouge. He said his mother knew before he was born that he had only one kidney, but beyond periodic screenings, his life has been the same as someone born with two kidneys.

He always loved football and played at Brusly High School for three years before graduating in 2015 from Port Allen High School with a 3.4 GPA and a 21 on his ACT. After playing defensive back for a year at Louisiana State University (LSU), he was recruited by USM coach Dan Disch to help rebuild a team that was losing key players to graduation.

As a transfer, Hammond knew he had to sit out for a year, so he sold his car for extra cash, took classes online and trained every day. Years earlier, he had dedicated his career to his great grandmother, who died when he was just 8 years old.

“She always encouraged me to do things as far as football and playing sports and things like that, so I kind of dedicated that to her and having that taken away is kind of like, wow, it hurt,” said Hammond.

“Any kind of struggles or anything off the field, when you get on the field between those white lines, it all goes away, it was my healing place,” he added.

According to the complaint, when USM trainer McCall learned Hammond had only one kidney, he referred him to a team doctor, who examined Hammond, confirmed he was healthy, but refused to him due to the “liability of this condition” to USM.

USM and Coach Dan Disch did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Determined to play, Hammond sought a second opinion from his kidney specialist, Dr. Raynold Corona, who in early August submitted a letter to USM clearing him to play.

According to the complaint, when McCall said Dr. Corona’s initial letter wasn’t long enough, the doctor spoke on the phone with McCall and submitted additional documentation detailing Hammond’s medical record.

In his second letter, Corona said that Hammond’s risks of a football injury to his kidney are “incredibly slim and I suspect he has much greater risks from driving around town in his car … I feel the patient should not be prohibited from playing football based on the presence of a solitary kidney.”

Hammond said USM still refused to let him play and refused to allow a third, independent medical opinion, instead relying on a doctor affiliated with the school who had decided — without examining him — that his playing was a “liability [to] the institution.”

In late August, with the start of the season quickly approaching, Hammond offered to sign a waiver of liability, which he said USM policy explicitly allows for when student athletes have pre-existing medical conditions. He said USM refused to accept the offer.

Attorneys for Hammond said they have obtained internal memos confirming that members of the USM athletic staff were concerned that his condition would create liability that could “be costly to the institution and Athletic Department.”

Fearing he was running out of options at USM and anxious to get back on the field, Hammond also contacted Middle Tennessee State University, hoping to play there if the situation at USM wasn’t resolved. He was stunned to hear that the coach was not interested and that the school had been told he had a kidney problem and didn’t pass a physical.

“That was almost bigger than telling me that I couldn’t play there,” said Hammond, who said his kidney is functioning normally and he’s never failed a physical.

“Not only did they not let him play at USM, but they tried to interfere with his ability to play somewhere else,” said William Most, one of Hammond’s attorneys.

“To disclose his personal medical information — even if it were true, which as Deven points out was not true — is a problem,” said Most, who added that federal law prohibits sharing an individual’s medical history without their prior permission.

Research shows the risk of injuring a kidney while playing football is extremely low and American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines support allowing athletes with one kidney to play if the single kidney is healthy and functioning normally.

“For every kidney injury, there’s 64 concussions and we have one brain and one spinal cord and one heart and kids play sports all the time with those,” said Dr. Matthew Grinsell, a pediatric nephrologist who reviewed data from the National Athletic Trainer’s Association and found kidney injuries in high school football to be extremely rare.

“Looking at it medically, I’m much more concerned about concussion and brain injury than I am about kidney injury when patients play these sports,” said Grinsell, who added that although risk of injury is low, it is not zero.

“If you have one kidney and you lose function, it’s definitely going to be a life changing event, because then you’re talking about dialysis and transplantation. It’s a big deal and I think that’s what people are worried about — but the question is, ‘how often does that happen?’ and we’re like, ‘we don’t know that that’s ever happened’. The evidence for that concern just isn’t really there,” he said.

In 2015, the NFL reported 197 concussions and just two kidney injuries. Neither injury resulted in the loss of a kidney. Giants cornerback Dominique Rodgers-Cromartie, who had a non-functioning kidney removed when he was a child, has played in the NFL since 2008 and has been an inspiration to Hammond.

“I think it should be the player’s decision as long as they understand the risks and are counseled” said Grinsell. “If they’re willing to accept the risks, then I say okay, as long as you are educated you should be able to play.”

Like Grinsell, Hammond said players should be the ones who decide whether to play or not and said no one should be made to feel handicapped by having others make that decision for them.

Although he isn’t playing this season, Hammond is back at LSU, studying business and computer engineering. He still trains every day — his training motto is if you stay ready, you don’t have to get ready — and is considering his football options for next year.

“I just want to get back to playing the game of football without this label over me as the kid with one kidney. I just want to be Deven Hammond the football player, not Deven Hammond the athlete with one kidney,” he said, adding that he hopes the lawsuit will prevent other athletes from being discriminated against due to similar conditions.

“The situation is bigger than me, it’s not just about Deven,” he said. “It’s about everyone else that comes after me at that university or anywhere else.”

This story originally appeared on Medium.