Questions the Press Needs to Ask About the Gulf Oil Disaster

A version of this blog first appeared on the Neiman Watchdog website

I have worked and lived with the people of the bayou in Buras, LA, for the past six months. But when the BP well from hell was capped in mid-July, the media ran for the exits as fast as they stormed the bayous in early May. They've barely looked back.

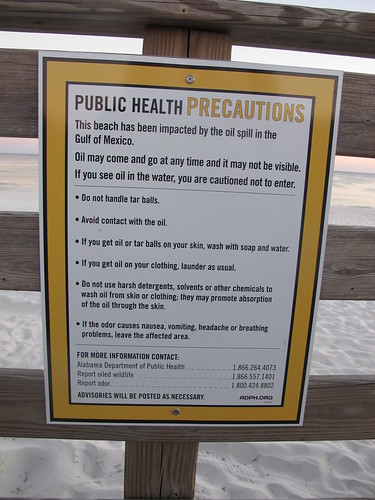

But unfortunately the oil did not go away. Oily sheen and tar balls still wash in with the tides, still pop up on the surface, and still threatens the livelihood of a culture that is disappearing with the sea-flooded marshes. Recently, I took a freezing boat ride out to the coast of the Mississippi delta and found tar balls still littering the beaches. According to cleanup workers out there, there's a constant wave of these weathered oil pieces washing in. They didn't expect it to go away anytime soon. Truth is, no one knows how much oil is buried on the ocean floor, sunk by chemical dispersants and rising slowly like a poisonous Phoenix.

Last week President Obama’s Oil Spill Commission issued its final report. It was well received by many residents of the Gulf, but people in the region still have huge health concerns as they deal a variety of physical and mental health ailments they say are tied to the oil and the two million gallons of chemical dispersants sprayed throughout the Gulf. This was topic number one raised by the public at President Obama's oil commission forum in New Orleans last week, a day after it issued its final report. Commissioners Frances Beinecke and Don Boesch heard an earful from coastal residents who have had enough of the government’s inaction and dismissive attitude. They promised to bring their concerns back to the president.

Cherri Foytlin of Gulf Change, a community organization based in Grand Isle, LA, gave an empassioned plea for help.

“Today I’m talking to you about my life. My ethylbenzene levels are 2.5 times the 95th percentile, and there’s a very good chance now that I won’t get to see my grandbabies…What I’m asking you to do now, if possible, is to amend [your report]. Because we have got to get some health care. I have seen small children with lesions all over their bodies. We are very, very ill. And dead is dead. So it really doesn’t matter if the media comes back… or the President hears us, or… if the oil workers and the fishermen and the crabbers get to feed their babies and maybe have a good Christmas next year… Dead is dead…I know your job is probably already done, but I’d like to hire you if you don’t mind. And God knows I can’t pay you. But I need your heart. And I need your voice. And I need you to come to that table. And I need you to insist that Feinberg and anybody else that needs to be in on that conversation comes too. And I’m asking you that today. And I would like you to say yes to me today. While you look me in the eye, please say yes you’ll come to my table.”

Latosha Brown, director of the Gulf Coast Fund for Community Renewal and Ecological Health, said this is a story her organization has heard repeatedly. “The key concern expressed by the community in response to the report is the overwhelming need for access to health care. Over and over, people exposed to crude and dispersants from the drilling disaster told stories of serious health issues--from high levels of ethylbenzene in their blood, to respiratory ailments and internal bleeding—and expressed an urgent need for access to doctors who have experience treating chemical exposure.”

So where's the press been on this? Except for a few independent reporters like Dahr Jamail, they've been mostly asleep at the wheel. While the federal government plans a five-year health study, residents say they don't have time to wait. Medical experts are in short supply down in the bayous and along coastal communities that have borne the brunt of exposure to the toxic soup that invaded their shores. "They can study all they want," says Venice, LA, community health advocate Kindra Arnesen. "People here need medical help now. By the time the government gets around to doing any study, it will be too late."

I've put a short list of questions Gulf residents are asking that are not well known by the rest of the country. They are important questions that the media needs to ask in its role as government watchdog and voice of the disenfranchised. It's a role that desperately needs to be filled.

Q. The economic impact of the BP disaster has hit the fisherman community especially hard, as their livelihood has been severely threatened. Many of these fishermen are subsistence fishermen who don’t keep meticulous records of their catch. How are they being compensated if they can’t provide adequate records? What safety net is there for people who have fallen through the cracks or have improperly been denied claims?

Q. Many cleanup workers complained of illnesses and sickness after working on oil cleanup last summer. Some were hospitalized. Some workers complain they were let go and still have medical issues, yet can’t get compensation for their medical bills. Who is responsible and how can cleanup workers, many of them former fishermen, be compensated and treated properly?

Q. The FDA and the EPA have been reluctant to share all government test data with independent scientists. Some independent scientists are reporting higher levels of oil contaminants in seafood tests and in sediments, some at alarming levels. How can the government continue to insist the seafood is safe when independent tests are showing these discrepancies?

Q. Minority communities such as Native American fishermen, Vietnamese shrimpers and African American oystermen have been hit especially hard, since they are not well plugged into the complicated claims process due to lack of education and professional assistance. Unemployment rates in some of these fishing communities is at 80%. These communities have few other options than fishing and living off the land as they have for generations. What has the government and BP done to reach out and help support these communities as they wait for their fishing business to return to normal?

Q. Shrimpers, oystermen and crab fishermen have reported oily substances turning up in some of their catches. Yet the government has only closed one area to one kind of fishing (royal red shrimp) when tar balls turned up in fishing nets. Many fishermen believe the oil is sitting on the bottom and will contaminate migrating bottom feeders such as shrimp. If these anecdotal reports of oil in seafood catches are true, why isn’t there more attention paid to them?

Q. The oil disaster has shined a spotlight on the Gulf marsh region that is rapidly disappearing. A huge amount of money is now being appropriated for Gulf restoration. Yet the political forces against restoring the marshes are still firmly in place: ship navigation up the Mississippi River; oyster fishermen who fight again increased fresh water flow; developers who stand in the way of restoration projects; etc. How is this restoration effort any different from the rest?

Q. Residents and cleanup workers continue to complain that chemical dispersants are being sprayed or used at night. Some Gulf coast activists claim Corexit compounds are still turning up in the water, and Corexit containers of dispersants were seen in dock areas long after the government and BP said they stopped using it. How can BP assure the public that its cleanup contractors are not continuing to use dispersants?

Q. After the Exxon Valdez disaster, research showed that over a period of years many communities were torn apart by social stresses, including increased divorce rates, mental health issues, crime rates and school dropouts. In areas hit hard by the oil disaster in the bayous, there is evidence this is starting to happen. What are government and social service groups doing about this problem and is BP paying for any of this?