Grand Isle Businesses Battered by BP Oil Disaster

For more than 30 years, Sarah and her daugher Annette Rigaud owned one of the most popular eateries on Grand Isle, LA. Sarah’s Restaurant is a cozy place filled with mementoes of sun-splashed beach vacations and fishing trips. It was a prosperous business, part of a proud family lineage that dates back to the colonial days of the 1700s here. The Rigauds have endured hurricanes, droughts, disease outbreaks and pirates that once roamed these marsh-filled ocean bayous.

Then the BP oil disaster washed ashore last summer.

After that, the Rigauds say business tanked by 75% as tourists who once flocked here abandoned the sandy beaches and rental cottages. In their place came legions of trash-bag carrying cleanup workers and giant yellow sand-combing machines that prowled the beaches scooping up oil. The Rigauds say their restaurant lost business because most of the cleanup workers had meals catered from out of town.

Sarah and Annette Rigaud, Grand Isle, LA photo by Rocky Kistner/NRDC

Like everyone else on this historic island, Sarah and Annette applied for relief from BP right after the well blew last spring. They say they received two checks for $5,000 each. When Ken Feinberg was appointed head of BP’s $20 billion claims fund in August, they thought relief was in sight. But instead, they say, Feinberg’s operation has put them through a maze of paperwork shuffling that includes months long reviews that go nowhere. Now they, like other businesses here, are on the verge of bankruptcy.

“It’s been a nightmare,” Annette says. “We’ve filed for claims but don’t even know what to ask for because no one in the claims office has the right information. Things change every time we turn around. This is not a game to us. We hope and pray that we’ll have money to pay to stay in business.”

The Rigauds say even big shots in Washington haven’t helped. Grand Isle mayor David Carmardelle spoke to congressional and White House staff about their case, but so far even they haven’t been able to help. “It’s crazy," Mayor Carmadelle says of the claims process. “Some people around here have gotten checks who never worked a day in their life, and others who have businesses here have received nothing. Feinberg is starting to act more like FEMA did (during Katrina) these days. Seems like the ones who are being honest are having the hardest time getting their money.”

Money around here is hard to come by today. The vacationers are long gone, but the tar balls remain. Beach cleanup continues at a much slower pace. People here say the oil is sunk on the bottom, coughing up pieces of hardened crude when the winds and the waves are right. No one here wants to think of what the hot summer will bring, when the water warms and onshore winds blow in any oil that floats to the top. Feinberg’s most recent claims report says Gulf fishing stocks will recover quickly, but other scientists question that (see NRDC’s David Newman’s blog on this here). The truth is no one knows what the oil’s impact will be on the wildlife and seafood in the years to come. But already there are signs it may not be good.

Karen Hopkins of Grand Isle’s Dean Blanchard Seafood, the largest shrimp buyer in Louisiana, says shrimp catches have been cut in half as many boats were unable to trawl through the oil last year. But what’s most worrisome may be what’s to come. Karen says no one has been catching a popular white shrimp people here call a “sea bob,” usually abundant this time of year. And no one knows why. “Normally we catch 200 to 300 thousand pounds of sea bob in the winter, but this year there’s been none. Even if we get shrimp this year, what will happen the next? It could take several generations for the oil to have an impact."

Karen Hopkins, Grand Isle, LA photo by Rocky Kistner/NRDC

Dead pelican, Grand Isle beach littered with tar balls. photo by Rocky Kistner/NRDC

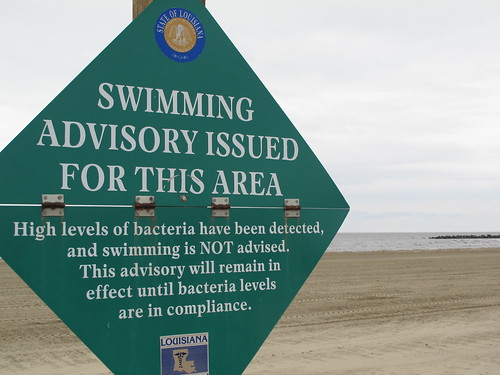

Warning sign, Grand Isle State Park. Photo by Rocky Kistner/NRDC

But fishermen aren’t the only ones worried. Small business contractors have been devastated by the drop in tourists, and many wonder if the tourists will ever come back. Take Betty Doud for instance. An experienced house painter, she said she used to have to turn down work in the summer in this usually bustling beach town. But no more. Business dried up for here right after the BP well blew, and the job she was working on was cancelled. Betty says after coming across dead turtles on the beach, she had to leave the area to collect her sanity. She returned last fall, hoping the beaches were clean and BP had really “made it right.” Instead she says she's come across oil, tar balls and giant waves of brownish foam on the beach that give her headaches. And adding insult to injury, Betty says, the claims office still hasn't paid her claim, losing paperwork and putting her in a seemingly permanent holding pattern.

A month ago Betty came across a fisherman on the beach who had oiled shrimp in his nets and who complained of burning rashes on his skin. Now she sees crews bringing in giant dump trucks of sand trying to bury the oiled sand on the beach. “They all want to bury it and say the coast is clear,” Betty says, “But the oils not going anywhere. We’re surrounded by it and it will just keep coming in with the tide.”

Betty Doud with tar balls, Grand Isle Photo by Rocky Kistner/NRDC

Oil tainted shrimp caught on Grand Isle Photo by Betty Doud

Places like Grand Isle are bearing the brunt of the environmental and economic impacts of this oil disaster. But it isn’t alone. From Panama City to Gulf Shores to Gulfport, businesses are teetering on the edge. Million-dollar advertising campaigns aren’t going to bring the tourists back. Pristine sand and oil-free waters will.

Business owners like Sarah and Annette Rigaud are praying for that this year. But when they look out at the offshore oil platforms in the distance, they are constantly reminded this disaster is not over. They know it could happen again. “We don’t want to bring our grandkids here,” Annette says. “We don’t know what we’re exposing them to.”

The Rigauds say they can handle disasters like hurricanes, just as generations before them. But a catastrophic oil spill is unchartered territory. They and many others are caught in a dangerous oil experiment in the Gulf. And no one knows how it will turn out.