Community Protests Toxic School Site in New Orleans

The Recovery School District (RSD) plans to build a new school on a toxic site in New Orleans, and it has the blessing of the state’s Department of Environmental Quality. But a lawsuit and growing community opposition seek to stop the plan.

The site in question, at Roman St. and Earhart Boulevard, housed the Booker T. Washington High School from 1942 until 2004. Before that, it was home to the Silver City Dump. Testing at the site has revealed dangerous concentrations of heavy metals such as antimony, arsenic, barium, cadmium, copper, lead, mercury and zinc. The RSD plans to remediate the contaminated site, build a new school, and populate it with students from Cohen College Prep High School, currently housed in the old Walter L. Cohen High School building.

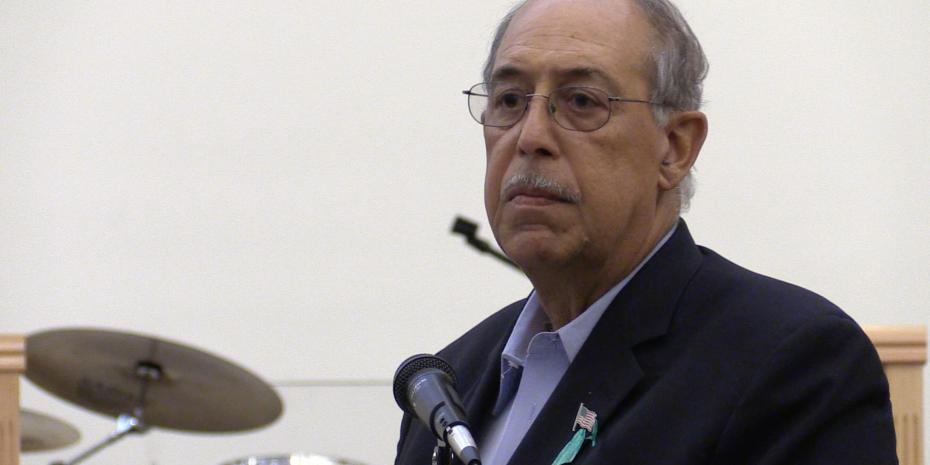

Photo: General Russel Honoré speaks out against the RSD's school building plan, at a community forum in New Orleans on June 26th.

But the plans to remediate the property are insufficient, says the Walter L. Cohen Alumni Association, which has sued the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). “We’re not anti building a Booker Washington school,” said James Raby, president of the Walter L. Cohen Alumni Association, at a public forum in New Orleans on June 26th at the Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church. “We are, we’ll always be, anti building any school on a contaminated site.”

Video Highlights of the June 26th Community Forum

Attorney Monique Harden, whose public interest law firm Advocates for Environmental Human Rights (AEHR) is representing the Cohen Alumni Association in the lawsuit, said the DEQ’s corrective action plan to clean up the site does not address how vulnerable populations – children, infants, nursing mothers, the elderly – who live nearby will be protected in the clean-up process, as required by law. “They completely ignore that there are people living on Erato Street. They completely ignore that there are people in Marrero Commons. We’re invisible to them,” she explained at the June forum, which was hosted by the Walter L. Cohen Alumni Association, AEHR, and the statewide advocacy group Green Army, and featured environmental scientist Dr. Wilma Subra.

Dr. Subra pointed to another major flaw in the remediation plan: RSD and DEQ struck an agreement in August 2013 that just the top three feet of soil at the site would be removed, even though contamination goes down 15 feet. She rattled off the health impacts associated with the heavy metals that would be left on the site: irritation to the skin, eyes, nose, throat, and lungs; headaches; dizziness; nausea; vomiting; lung; liver and kidney damage; cancer; reproductive health damage; nervous system damage; and more. Subra said these heavy metals will find their way not only into students and teachers on the site, but also the remedial workers, construction workers, parents, and community members around the school.

Protecting the Environment or Fast-Tracking Industry?

The problem, argued retired U.S. Army General Russel Honoré , lies with the Department of Environmental Quality and the laws that govern it. “They give exceptions and exemptions to the Clean Water and Clean Air Act. Their job is to help industry.” General Honoré, who heads up the Green Army, a statewide coalition to challenge the oil and gas industry in Louisiana, said that rather than regulating the Recovery School District’s plans, “DEQ will give that exception if that’s what the RSD wants.”

He referenced environmental health disasters across the state, “[RSD] defer[s] to the DEQ, who approved Bayou Corne, who said yes to go frack up in St. Tammany Parish, who said yes to the water in Mossville… It’s the same DEQ.”

Audience members at the forum brought up other examples of African American neighborhoods in New Orleans being situated next to heavy industry and waste. Reverend Lois Dejean said: “I know when DEQ wanted to clean up in Gert Town, it only cleaned up to a certain level. You can’t put a house on… You can’t put a toilet on it! So you know you can’t put a child on it.”

City Councilwoman Nadine Ramsey assured the community she would be “keeping a close eye on this case.” As a judge, Ramsey ruled that the city of New Orleans was negligent in building homes (which were marketed and sold to African Americans) and an elementary school on top of the Agriculture Street Landfill.

“It’s like déjà vu… Whenever you talk about a landfill, we can talk about remediation, we can talk about the effects of chemicals, but the bottom line is, we don’t know,” Ramsey said.

Land Grab?

Why, many in the audience asked, would the RSD close Cohen and build a new school when the Cohen site is not contaminated? “It’s a land grab,” said Raby, pointing out that the land value at Cohen is about $2.7 million, compared to $700,000 at Booker T. Washington site (before they found contamination). He called on the RSD to build a new school at the Cohen site.

Raby recalled the history of the Booker T. Washington school. Built between 1940 and 1942, before the Brown v. Board decision found segregated schools unconstitutional, it was the second Black high school in New Orleans. “We’re going to build a school on a dump, take it or leave it,” Raby said the choice was at that time. “Well, it had been some 35 years [since McDonogh 35, the first Black high school in New Orleans, was built], so we said, ‘Fine, we’ll take that school even though it’s built on a dump’… Something beats nothing."

He added, “Though my daddy had to take it in 1940, I don’t have to take it in 2014.”

RSD and the Mayor’s Office Respond

Dana Peterson, with the Recovery School District, was given the opportunity to respond: “Mr. Raby implies there is a land grab. I don’t know. There are a number of buildings in the city that are surplus, land banked, the system no longer needs. The system sells those buildings, generally speaking to private interests, takes the resources, invests it in school and kids. That’s what happens.”

He insisted that the RSD would not deliberately put children in harm’s way, noting that the federal government would have to approve the plans before rebuilding (because FEMA money is involved). Peterson said if the remediation plan gets state and federal government approval, “We would have explicit confidence that what we would be moving forward with would be safe.”

But Harden pushed for more from RSD, saying, “The response ‘Well, we’ll wait for someone else to tell us no’ is not one that looks like community cooperation or respect.” She urged RSD to work with the community to find “a new way forward”, and called on the Mayor’s office to champion an ordinance that would prevent issuing building permits to schools on areas with toxic concerns.

Peterson and a representative from the Mayor’s office said they were open to dialogue.